Well, I did back in 2013 while I was in Ibadan. We were doing some research on Traditional African Communication Systems as a part of our postgraduate programme and found ourselves in the home of ‘Baale’.

Baale was the chief priest of all worshipers of ‘Sango’, a deity worshipped as the god of thunder. However, he wasn’t just a priest, he was also a designer of masquerade costumes.

His residence was a typical ancient Ibadan duplex, built with mud but plastered with cement. After a few moments of waiting, he welcomed us into an average-sized room where the costumes were made.

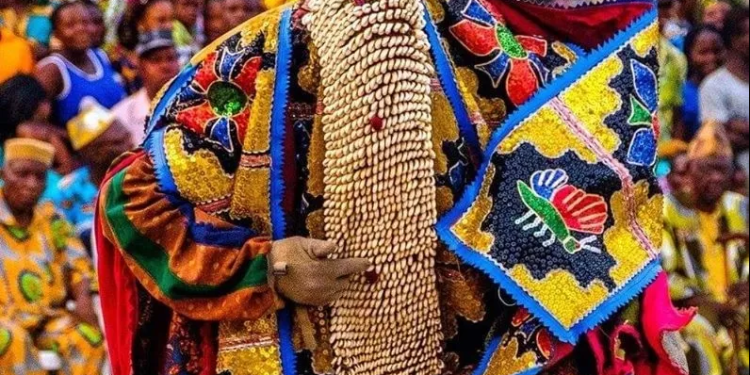

There was a large table in front of one of the windows. On it, were piles of clothes of different fabrics and colours (red, yellow, gold, silver, and some shiny fabric). There were also some wooden carvings, thread, and scissors on the table. Empty containers of gin and schnapps littered the floor.

We saw two sewing machines near the table on the right side of the door which had small earthen pots hanging from it. Tree barks lay in various corners of the room as well as wood carvings, one of which was deep brown and glossy. We were told it had been soaked in 21 different herbs for eight days and was now imbued with spiritual energy. Baale said the carving could be worshipped as a god and sacrifices made to it.

After some time casually chatting with ‘Baale’ another man joined us. We found that he was an Ifa (divination) priest, and he joined in answering our questions.

Baale had been in business for half a century. He was born into the trade and his father introduced him to the art as a child, so he didn’t go beyond primary school. His grandfather was a masquerader and the masquerade ‘Olukoyi’ was passed down in his lineage.

Business was at its peak when the festival approached. Then, apprentices would come around to work for daily pay. There are times when workers or assistants are required to wear the costumes, especially when the design requires it to be sewn upright or when finishing touches are to be done. Some of these apprentices were also masqueraders who come around to support the design process.

We wondered why masquerades were still a thing and as if reading our minds, Baale maintained they were still significant, saying that they dispel diseases. “As they walk or dance through the streets, they wipe banish epidemics like cholera, chicken pox, smallpox and all kinds of fever,” he said.

The Ifa priest added that masquerades contribute to the general well-being of the state. By bringing both spiritual and environmental peace.

“Egungun is an indispensable part of our culture and should not be trivialised. Once, a masquerader converted into another religion and got blind and it wasn’t until he wore his costume that his sight was restored,” he said, adding that there were other stories of families who suffered losses because they abandoned their masquerades.

When asked about Baale’s concern for his reputation because of his job and religion, he was unbothered, saying that while there were people who distanced themselves from him, those that are close to him know his value.

After the interview, Baale showed us another room where he kept costumes and other completed designs. We were asked to remove our shoes before entering and I took the extra pain of entering left foot first (call it superstition). In the far-right corner, we saw the costume of Baale’s masquerade – Eegun Adinimodo (or Olukoyi). It had a large wood carving of a man’s head on top, with four other heads around the neck. There were layers of different fabrics of varying colours stemming from the head.

One would have assumed that someone was being trained to take up the mantle but when asked about how well the next generation receives the art, Baale wasn’t keen. Although his sons knew the trade and assist him occasionally, their focus was elsewhere. He had a son at the Polytechnic who was also involved in local politics but still engages in the art. When the time comes for the festival, the young man would design his own costume, sew it and go out for his performance.

Once we were done, we presented a little gift to him and took our leave.